Our Stories

Men from the community of Akhiok, Easter Sunday 1928. Courtesy of the National Archives, Alaska Schools Album.

Imaken Ima’ut—From the Past to the Future

Museum staff members discuss the past 300 years of Kodiak history and the ways Alutiiq life changed. Created with support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Created with support from the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

Learn More

This free eBook shares Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history from the time Alutiiq people arrived in the archipelago till the present.

These one-page lessons explore topics in recent Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history. Download a copy to continue learning.

Deep History

Archaeological finds suggest that ancient Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history (7500 to 250 years ago) can be divided into three cultural traditions – ways of living.

Ocean Bay Tradition – Kodiak’s first residents arrived at least 7,500 years ago, colonizing an environment warmer and drier than today. Archaeologists believe these people came from southwestern Alaska and were well-adapted to life along the coast. Like their descendants, they used barbed harpoons, chipped stone points, and ground slate lances to hunt sea mammals, delicate bone hooks to jig for cod, and large bone picks to dig for clams. Early residents probably lived in both skin-covered tents and oval, single-roomed houses with sod block walls.

Kachemak Tradition – About 4,000 years ago, Kodiak people began to focus more intensely on fishing, harvesting quantities of both cod and salmon. They developed nets to harvest large quantities of salmon, and slate ulus and smokehouses to process the catch for storage. Over time, the island’s population grew and filled up the landscape. By the end of the Kachemak tradition, people were trading for large quantities of raw materials from the Alaskan mainland. Antler, ivory, coal, and exotic stones were manufactured into tools and jewelry. Labrets, decorative plugs inserted in the face, became popular at this time, perhaps to signal the social ties of the person wearing the labret in a landscape where there was increasing competition for resources. The first signs of warfare appear in the Late Kachemak.

Koniag Tradition – About 800 years ago, fishing grew even more important as people harvested even greater quantities of salmon to feed their families and trade with neighbors. Related families began living together in large, multiple-roomed sod houses pooling resources and labor. Chiefs emerged, perhaps to organize labor. They led war and trading parties and hosted elaborate winter ceremonies to display their wealth and power, honor ancestors, and ensure future prosperity.

This way of living persisted until the final decades of the 1700s, when the arrival of Russian traders swept the Alutiiq into the global economy and irreversibly changed the culture.

Learn More

Story of a Bear Camp

The Helgason Bear Camp, Uganik Passage, 1963. Photo by Ralph Hawkins, Courtesy of the Helgason Family.

For more than sixty years, members of the Baumann/Helgason family lived on the shore of Uganik Passage, mining, gardening, harvesting local resources, and guiding sport hunters. The Helgason Terror Bay Camp was one of the first lodges in the Kodiak region and known for its hospitality. William Baumann developed the property starting in the 1920s. His daughter Clara and her husband Kristjan Helgason inherited it in 1945 and family members lived there until 1990.

“…their bear guiding camp was a little bit different from some of the other ones because it was more like a home…”

—BRENT WATKINS, TERROR BAY NEIGHBOR, 2024

Quluryaq

Quluryaq is the Alutiiq name for Terror Bay and Uganik East Passage. This mountainous region has a dense cover of grass and brush and valuable land and ocean resources—bears, salmon, shellfish, and birds.

Quluryaq has a long human history, from its use by Native fishermen to recent settlement by miners and bear hunters. Today, it is part of the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge and a popular recreation area.

Ancestors

Alutiiq/Sugpiaq ancestors lived beside Quluryag thousands of years ago. One of their settlements was on the shore near the Helgason camp. Here there is a thick deposit of midden—shell, animal bones, and tools. Cobbles used as net weights and slate ulus used for butchering suggest residents harvested salmon with beach seines and cleaned their catch. Fishing probably took place in late summer when salmon are plentiful here.

Remote Mine

In the early 20th century, American settlers explored Kodiak Island for mineral deposits. William Baumann, an agricultural worker from Minnesota, registered a mining claim in Uganik Passage with two partners. In the 1920s, Baumann and his wife Elizabeth Kalmakoff, an Alutiiq woman from Kanatak, built a log cabin south of their claim. Here the Baumann’s spent their retirement years gardening, keeping chickens, and prospecting.

Family Guiding

In 1941, President Roosevelt created the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge to protect brown bears. A regulated annual bear hunt, led by licensed guides, became a part of wildlife management in the refuge. Clara and Kristjan Helgason used their remote home as a bear camp. The couple, their son Leonard, and Clara’s brother William Baumann, Jr. worked together. Later they were joined by Leonard’s son Steven. Guiding provided income, but it was also a lifestyle. The Helgasons lived in Terror Bay for much of the year.

Hospitality

For the Helgasons and their guests, visiting Terror Bay was as important as the hunt. Sportsmen came from across the United States and even the world to hunt brown bear and black-tailed deer. They traveled to Terror Bay on a small amphibious mail plane. The Helgasons led 10 to 12 days of hunting and excursions. At the camp, visitors found a warm home full of local stories and subsistence foods. Clara enjoyed serving meals to her guests.

Clara Helgason

“We had some deer hunters from Anchorage, the banker, Ed Rasmuson. They all had just a wonderful time out there. And we got a letter from Ed Rasmuson, thanking us for having such a wonderful time. They said ‘We’ve hunted in many camps and that’s the nicest camp in Alaska.’ It just made us feel so good, you know.”

—CLARA HELGASON, 1972

Steve Helgason

“She took pride in feeding the hunters and taking care of them. The hunters, they all loved Kristjan. My grandfather, he was a really good storyteller. He enjoyed all the hunters… It was a jolly time around the dinner table back in the days. They got to eat good meals. They got to taste the land.”

“I just remember the good times and I have fond memories of it. It was a good experience being out there…”

—STEVE HELGASON, 2024

Homestead

When the bear season ended in May, the Helgasons commercial fished, harvested subsistence foods, and tended their gardens. The family lived in Kodiak and Anchorage, returning to Terror Bay in the summers. After losing her husband in 1977, Clara kept the remote camp going. She cooked for guests into her 80s while her son and grandson guided and fished. In the early 1990s, Clara retired from remote life. She sold her property to the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge and spent her final years in Kodiak.

Presentation

Archaeologist Molly Odell discusses the Alutiiq Museum’s study of the Helgason Bear Camp — its archaeology and recent history — in this videotaped lecture.

Learn More

Produced with support from the US Fish & Wildlife Service and photos from the Helgason family.

Daniel Harmon—Alutiiq Hero

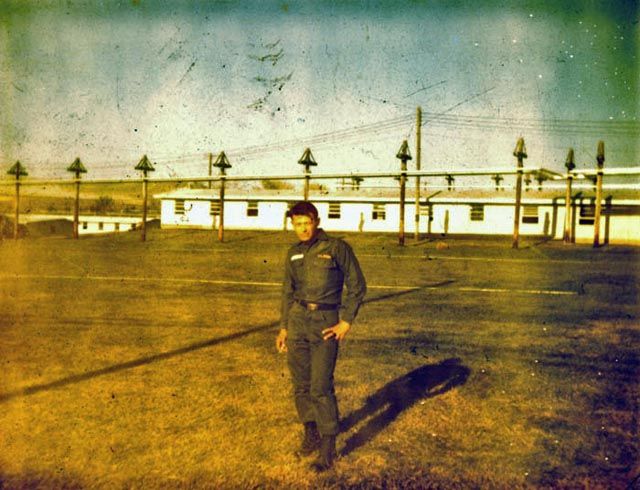

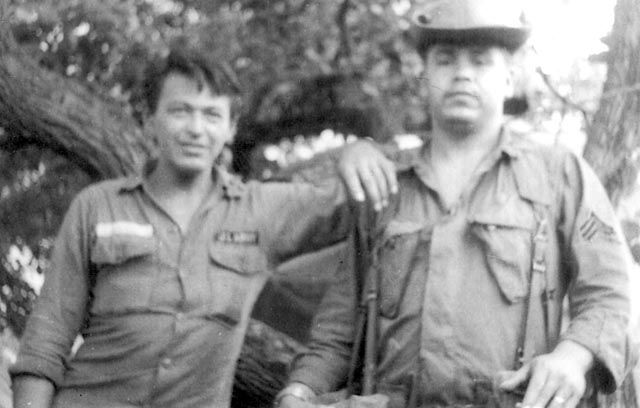

Daniel Harmon in Vietnam. Harmon Collection.

Native American people have served in every major American conflict since the Revolutionary War. Daniel Lee Harmon was an Alutiiq man from Woody Island, Alaska, who volunteered to serve his country by fighting in the Vietnam War. Throughout his tour of duty, Daniel showed courage and valor. At age 21, he made the ultimate sacrifice. Daniel was killed while trying to rescue a fellow soldier after helping another injured soldier to safety.

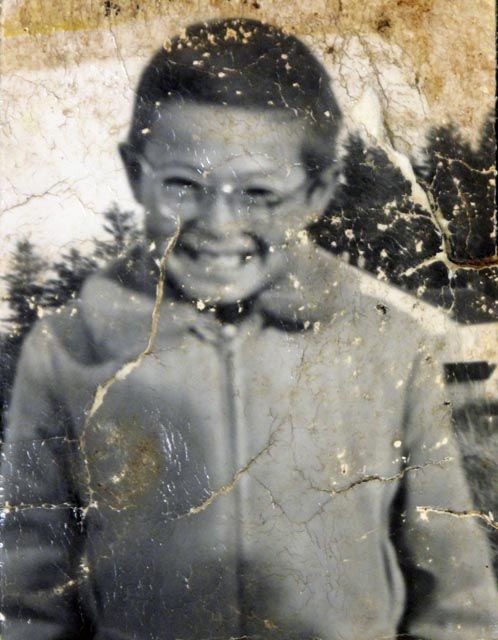

Childhood

Enlistment

As a young man living in Kodiak, Dan volunteered for the Alaska National Guard. During basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington, Dan spent weekends with family members living nearby. This included his brother, Mitch, and his niece, Margaret. They remember Dan’s big smile and his grin as he waved goodbye each Sunday when they dropped him back at Fort Lewis. Dan was known for his sense of humor and a smile that put people at ease. Despite Dan’s easygoing spirit, he was very serious about going to Vietnam. When he discovered his unit would not be sent to Vietnam, Dan went absent without leave (AWOL) for a day. He insisted on going, and in July of 1966, he began his tour.

Service

In February 1967, Harmon volunteered for the Army’s Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP). He was assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. When the 4th Infantry Division moved into Central Highlands of Vietnam in 1966, they became responsible for covering the largest, most remote and treacherous area of the country. Dan volunteered knowing the danger and he participated in numerous patrols, some involving ambushing small groups of opposing forces.

Bronze Starr

|

On a mission in February 1967, Dan was the radio operator on a four-man team. During their patrol the team located an enemy mortar squad and noted their movement toward a U.S. Infantry base. The team acted quickly, relaying the likely location of the enemy squad and the base bombarded the enemy position. The enemy squad spotted the Dan’s team. Dan summoned artillery support and accurately adjusted the position to provide them enough cover for a helicopter evacuation. For his actions, Dan received a Bronze Star for heroism. In March 1967, on a patrol, Dan was wounded in both legs. His team left him behind, but he crawled to safety during the night. He was awarded a Purple Heart his the injuries. |

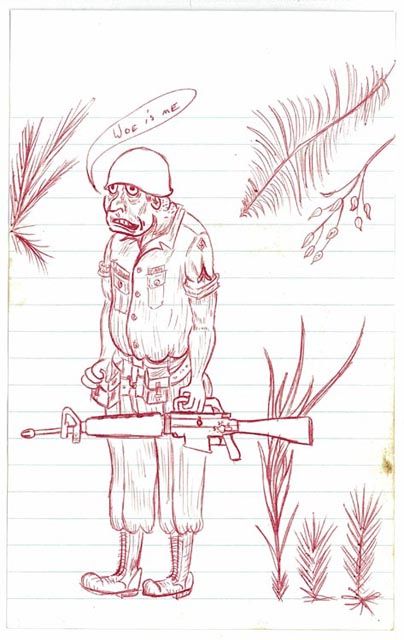

Letters Home

Dan’s letters to his sister, Leanna, reveal his sense of humor as well as his artistic abilities. Jim, Dan’s brother, remembers Dan’s drawings. He could replicate any illustration from a book and sketched on many of his letters home. From complete sketches to doodles, each picture shows his wit. In closing one letter, Dan drew a film reel using red ink and wrote, “The End – A Dan Harmon Production – in color – yuk-yuk.”

Final Battle

In late May 1967, Dan’s unit was ordered to carry out a damage assessment mission. Recently released from the hospital, and with just five days left of his tour, Dan volunteered to serve as the assistant team leader.

After spending the night in enemy territory near the Cambodian border, the team encountered a North Vietnamese Army squad and called for extraction. The Army deployed three tanks and an infantry platoon. As the tanks arrived, the team realized they were in the middle of a mine field. Enemy forces began detonating the mines damaging the tanks and injuring many. Harmon dragged a fellow soldier to safety and was attempting to save another when he was mortally wounded. He was 21.

Remembering Dan

In June 2003, family, fellow soldiers, and friends gathered on Woody Island to remember Dan. A Russian Orthodox memorial service honored Dan and his cousin Fred Simeonoff, a helicopter pilot who also died in Vietnam. Dan and Fred, both Alutiiq men, were the only two Kodiak casualties of the Vietnam conflict.

Recognition

During the week of the memorial service, fellow soldiers spent time getting to know Harmon’s family. In their conversations, they realized Dan had not been recognized for his actions. One of them spent three years gathering information and completing paperwork. Finally, in August 2007, over 100 people gathered at a memorial service to honor Dan, who was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star with the “V” device for Valor and oak leaf clusters – his third decoration.